Fields & Sectors: Wisdom & Practice (Part 1)

Alt Title: Field sensing, field building, bridging, field practice, and lived experience

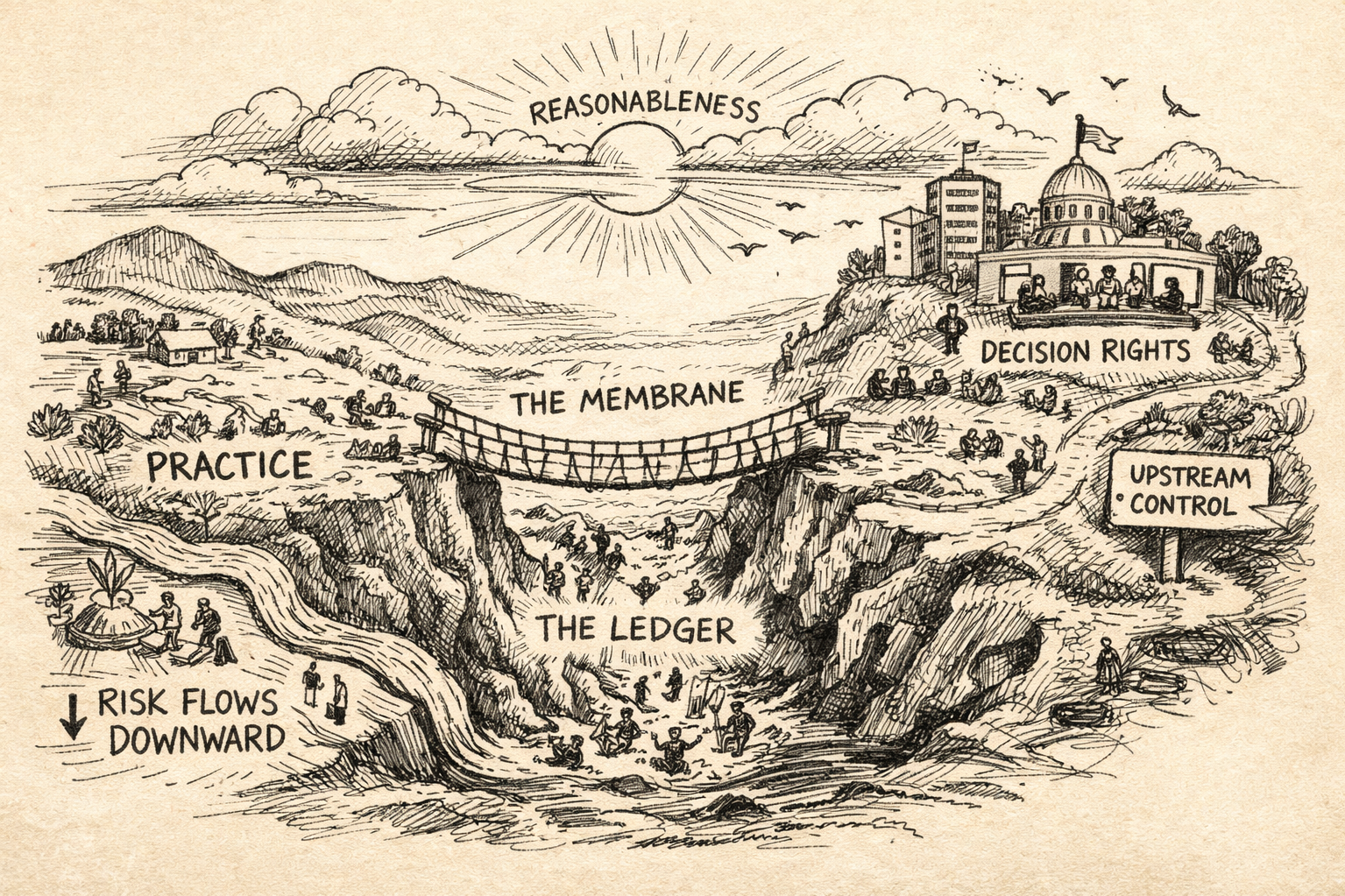

Visual depiction of terrain showing the field(s) of the conversation and bridging and differing depth and breadth of impact. (AI Generated)

The terms field building and field sensing show up a lot in the circles and networks I inhabit and then more latterly field bridging and naming the (often under-resourced) relational infrastructure has occurred. There is tension in how insights are arrived at, presented and platformed.

I wrote this reflection piece partly for my own sense of recalibration to what these concepts mean and also partially to connect to my evolving stance and understanding of why it matters that there is insufficient inclusion of power dynamics and ‘games within games’ that form the ongoing patterns we see in our work. The essay is an attempt to examine the structural architecture beneath the tensions.

The figure above illustrates the terrain we will cover/ traverse in this essay. The essay answers exploring the following questions:

what makes a field a field?

what are the differences between field building, sensing and bridging?

practitioners - who is ‘doing the doing’ in these practices?

the social sector - is it a sector? What makes it a sector and not a field

A game ecology is introduced to show how, in current state, something is being maintained not just described (systemic complicity, private loss of air, risk asymmetry, congratulatory coherence). The problem statement of this essay is that “authority remains centralized while consequence is decentralized.” This essay intends to make visible the emotional and ethical stakes inherent in the ecology. Structural compression causes internalized asymmetry which shows up with emotional clarity as absorbing moral residue without re-distributive authority in silence and isolation (private loss of air1)

Towards the end the reflections shift to games at play in field discourse and in the social sector. We examine yielding membranes and how fields redistribute power and resources and capitals (and decisions). We include two stark and two subtle illustrative case study examples to illustrate the point and close with a redistribution ‘test’. Namely, who decides? who bears cost? what would have to move in context, or primacy?

What makes a “field” a field

A field is a structured social system organized around a shared problem space. A field exists when coordination, competition, and meaning-making happen because actors recognize each other as part of the same system. The following core criteria (widely supported across sociology and systems theory) evolve a domain into a field:

Shared object of concern

Actors recognize they are working on the same underlying problem, even if they disagree on solutions. Example: “Climate mitigation” vs. “energy.”Recognizable set of actors

There is a relatively bounded population of organizations, professions, funders, regulators, researchers, and intermediaries who acknowledge each other’s relevance.Common frames and language

Shared concepts, metrics, narratives, and categories—even if contested. Fields tolerate disagreement; they do not require consensus.Rules, norms, and power relations

Formal or informal rules shape legitimacy, authority, funding flows, and influence. Someone can “win,” “lose,” or be marginalized.Reproduction over time

The field persists beyond individual projects or organizations through training, funding cycles, institutions, and reputational memory.

What is Field Building?

Field building happens when someone believes the field should exist or should function differently. It is normative and directional. It is an intentional intervention to create, strengthen, or transform a field.

Field building is future oriented. It assumes the ‘building’ addresses underdevelopment, fragmentation, or misalignment.

Typical activities in field building include:

Shaping narratives and problem framings

Legitimizing new roles or forms of expertise

Seeding institutions that stabilize coordination

Funding infrastructure (data systems, convenings, training)

Establishing shared definitions, standards, or metrics

Creating intermediaries, networks, or professional associations

The posture of power in field building is explicitly political, even when framed as “neutral”. That means there are decisions about who belongs, what counts, and which futures are plausible

What is Field Sensing?

Field sensing is diagnostic and not explicitly prescriptive in its intent. It is systematic observation and interpretation of how a field is currently functioning and changing.

Field sensing is oriented in the present and near-future. it is also continuous and not episodic; although, there may be fluctuations and oscillations in its prominence and foregrounding at particular junctures in space and time.

Typical activities in field sensing include:

Detecting early signals of change or fragmentation

Surfacing tacit dynamics that formal metrics miss

Mapping actors, roles, and relationships

Tracking shifts in narratives, norms, or funding flows

Identifying emergent tensions, gaps, or power asymmetries

The posture of power in field sensing is often a framing of neutral, objective, reflection. This is political, because (1) positionality absents the senser from the context and (2) what one chooses to notice shapes subsequent action.

What is Field Bridging?

Field bridging is the interpersonal and collaborative/co-operative work. It is the human and relational work that allows things to move between and beyond the other two practices of building and sensing.

Field bridging is intentional, relational and translational work that connects actors, knowledge forms, and power centers within or across a field. Bridging is not about shaping the field (like building) or interpreting it (like sensing). It is about translating across [and beyond] its internal boundaries — especially between practice and authority.

From a temporal perspective, field bridging is present and ongoing. It operates in the immediate moments ( of frictions, of capacity constraints, of ambiguity, etc. ) and it is continually practiced.

Typical activities in field bridging include:

Translating practitioner knowledge into funder-, policy-, or research-legible formats

Carrying knowledge across organizational, sectoral, or ideological boundaries

Absorbing ambiguity so coordination can continue

Holding relational continuity during periods of tension

Repairing trust after misalignment or harm

Reframing conflict so it can be metabolized institutionally

Designing and facilitating convenings that allow disagreement without rupture

Drafting synthesis memos that soften sharp edges without erasing substance

Translating governance constraints, fiduciary logic, or political realities back to practitioners

The posture of power in field sensing that it exists between sensing cycles and building cycles. It is ‘mixed-horizon, short-cycle and iterative rather than long-horizon strategic. It may come off as episodic but it is constant in practice. Actually ‘good’ bridging is deep sensory-weaving work. Field bridging does not shy away from fragmentation, mistrust, or asymmetry are ongoing conditions. However it is quite often performed by some more than others (again see power dynamics) and is invisible (or invisibilized) in formal timelines.

How does bridging work in a field? As an example, someone recognizes fragmentation, asymmetry, or misunderstanding and steps in to do the relational work with a desire to enable coordination without necessarily redesigning the field itself.

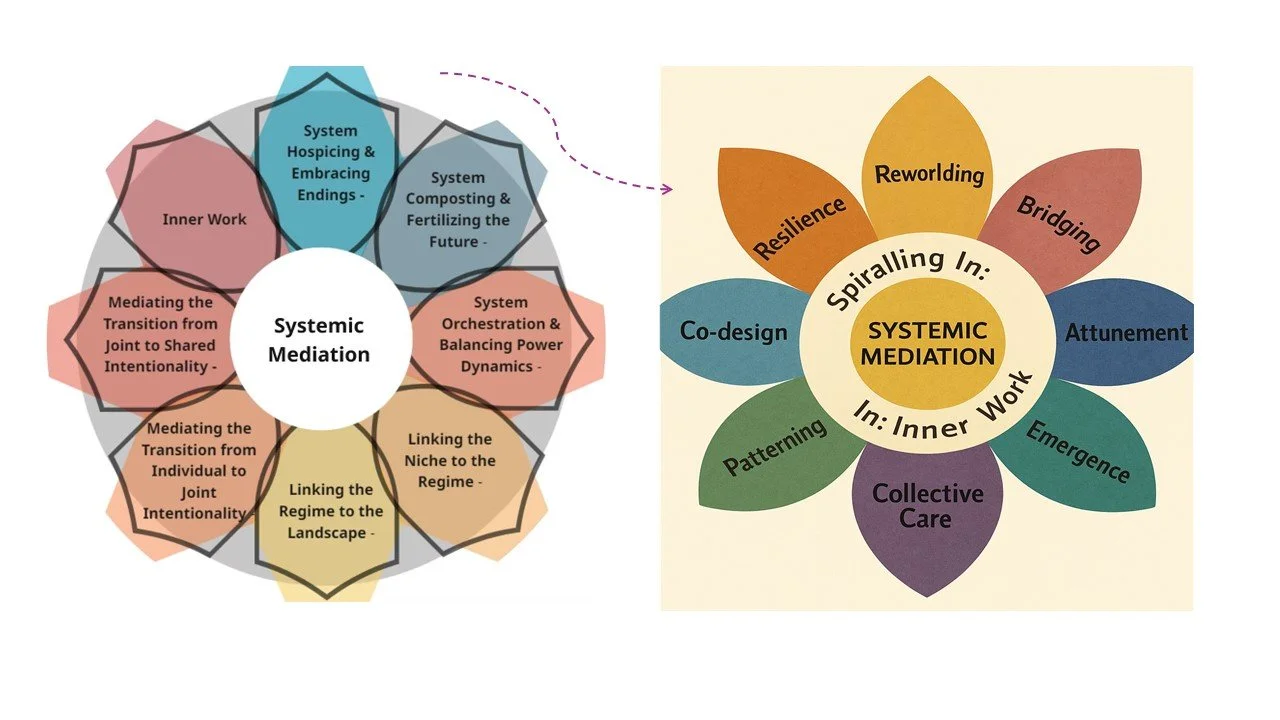

It is connective and mediating. Ideally field bridging enables actors within the field (or across fields) to understand, tolerate, or act with one another. At Transition Bridges Project we have been exploring the ways in which systemic mediation acts in bridging at many scales, including fields.

Field bridging is metabolically expensive; it is happening in the meeting, and before and after. It happens in the hallway conversations and the group chats and the noticing who stepped out for some air or a break.

Bridging is structurally precarious; rarely holding final decision rights. It usually operates in a liminal power position. It is close enough to authority to be heard (until it is silenced). it is close enough to consequence to feel cost (and in relationship to those who will be impacted by directional decisions for future action).

Bridgers can sometimes feel isolated, like they are betraying ‘all sides’. They carry responsibility without authority, credibility risks in all directions of their relationships (especially as they hold tensions and ambiguity and can seem to be appeasing one side or other). Perhaps most detrimental is that bridgers while working to prevent rupture could do so at the cost of redistribution of resources (power and other capitals). As weavers, often across multiple networks, they are critical to field functioning but poorly resourced and often burned out, because their value lies in relationship and trust, not artifacts.

The first 8-petal flower in this image represent the Areas of Work that Transition Bridges Project has been working with in our Systemic Mediation practice. The second 8-petal flower provides an illustrative example of bridging where the technical terms in the initial image are evolved into more active terms for the Areas of Work, and inner work is understood to permeate them all.

Practitioners - who is ‘doing the doing’

Most “field” discourse is written about coordination and cognition, not about practice. The practitioner(s) disappear depending on whose vantage point is being used in discussing the field. The field practitioner role is usually collapsed into other labels in ways that erase its field-level significance. Labels include but are not limited to grantee, implementer, front-line worker or organization, professional, activist, and ‘others’ *literally + as a continuation of this list :-)

A field practitioner is an actor whose primary activity is the repeated enactment of practice that directly engages the field’s object of concern. The work of a practitioner:

operates at the site of action, not coordination

produces outcomes, not alignment

often cannot be paused to sense or build without external support. *AND they are likely often the bridgers as this is not externally resourced

Field practitioner work is essential, their knowledge is procedural, tacit, and situational. Practice, repeated, recognizable practice, holds fields together. Especially before alignment with, and by, institutions in resourcing and supports.

You cannot sense a field that is not being practiced.

You cannot build a field that no one can enact.

Practice, is also the place where failure is first visible.

Practice is not easy to aggregate and is epistemically undervalued. Field knowledge privileges (1) Conceptual clarity over situational judgment, (2) Explicit strategy over improvisation (unless it is theorized and risk limited depending on who is speaking about it) and (3) Fundable abstractions over lived constraint

From a power posture perspective, centering practitioners in field discourse would force acknowledgment that:

Practitioners routinely absorb systemic contradictions

“Capacity gaps” are often structural impossibilities

Many field failures originate upstream (funding design, governance, metrics)

Fields begin with practice but authority (& legitimacy?) begins at building. Field bridging is the contested terrain between practice, sensing and building. If field bridgers coordinate with practitioners and builders (or sensors) simultaneously, they can either:

Protect coherence

Or shift authority

And neither of these choices neutral.

The figure at the beginning of this essay is illustrative of the many actors and actions/ happening across the terrain.

The social sector - is it a sector? And, why isn’t it a field?

The social sector is a sector that holds many fields. It is the container a container which organizes funding, governance and legitimacy. A space in which organizational forms + funding logics + governance norms + moral language & many fields live.

That fields live inside, across, and against the ‘social sector’ container is a distinction which becomes important in diagnosing why

consultation is mistaken for decision,

and sector-level “infrastructure building” is mistaken for field-level authority shift.

(But) if the social sector is not the arena (field), then where does the arena actually live?

Fields do not float inside a single container. They form within a broader political–economic ecology — where state power, market capital, philanthropic governance, professional authority, and lived consequence intersect. The social sector is one governance container within that ecology. It organizes legitimacy and resources. It does not exhaust the arena.

To understand why authority remains centralized even as critique circulates, we have to look beyond the container, even as critique circulates. We have to examine the ecology (state/market/social sector interactions). But ecology alone does not explain stability. Fields are filtered (selectively permeable) systems not open systems. This means that filtering happens between (1) consequence and authority, (2) lived experience and standards, (3) decisions and liability. In this essay that selective interface, that structure is identified as a membrane.

Structural Membranes and this essay’s Ecology

The concept of membranes as used in this essay does not mean biological or emotional metaphor but as structural filter(s). In ecological systems, membranes (permeable and semi-permeable) allow for selective permeability, regulating exchange and therefore maintain coherence without overload. In this essay, membranes become the selective interface between practice and authority/ legitimacy, lived experience and standards (active or passive) and lastly, decision rights and decision consequences.

(But) if membranes filter, what crosses from lived consequence into decision, the question becomes about stabilization: how do these structural membranes remain stable?

They remain stable through patterned coordination. And in this essay we call these patterns games. Games are this essay’s membrane-stabilizing strategies.

What is all this about Games?

I love board games, espcially strategy games and I also enjoy working on puzzles. It was natural then that I would consider how games might play an illustrative and illuminating role in this writing. I also share some poems but that is not until the very end, so keep reading, smile.

In asking the questions: Who builds? Who senses? Who Bridges? Who practices?What travels as evidence? What disappears? and Who decides? What we have not perhaps considered enough is that the answers to these questions are very grey and subsumed. In other words there is a lot of indirect activity connected to the answers to these questions. The activities of the actors who are ‘doing the work of these is mediated through games; the repeatable patterns of strategic interaction shaped by incentives, legitimacy, and risk. A field is less a system of roles than a stack of overlapping games that determine:

who gets to speak as the field,

who absorbs failure,

and how practice is translated (or not) into authority.

These are the games we will look at in greater detail in the next installment of this essay:

Visibility Games - What becomes visible as “the field,” and what remains background noise? *And what does visibility shape, and what are the impacts of invisibilization and erasure?

Legitimacy Games - who gets to define what is “real” “promising” “serious,” “rigorous,” “field-level” and yes “legit” :-) What is ‘filtered out’ or soften (lived contradiction, ethical discomfort, and negative capability)because it threatens ‘legitimate’ coherence.

Containment Games - how disruptive knowledge is acknowledged without letting it reorganize the field? Practitioner and first-voice knowledge is included, but ‘managed’ & carefully scoped.

Translation Games - what must knowledge become in order to travel? *OK, usually the direction of travel is upwards; but then there is an additional question of whose knowledge gets to travel in what direction, and how and why?

Risk allocation Games - Who pays (and to what extent) when theory meets reality?*If practice fails, who is blamed (and de-ligitimized, and expendable) and who gets to revise the theory?

Games as discussed in this essay are not random behaviours or outside of the ‘fields of play in this terrain’. The games becomes the invisible but very present and prominent coordination and organizing strategies for the roles and the ecology of this terrain.

Concluding Thoughts of Part 1 of the Essay

As we have traversed the terrain of fields, sectors, and the invisible games that stabilize authority and consequence, it becomes clear that the architecture of social systems is shaped not only by formal structures but by the lived, relational work of practitioners and bridgers. The membranes, but the ecology and the games that sustain it. This essay has mapped the contours of these dynamics; the next step is to explore how change might be enacted within and across these boundaries that regulate exchange—between practice and authority, experience and standards—are not fixed; they are sites of ongoing negotiation and contestation. If we are to move toward greater redistribution of power and resources, we must interrogate not just the container.

We will stop here and share some footnotes to further contextualize concepts in the essay and share useful sources and writings from which my reflections and re-calibrations emerged (or diverged?)

In Part 2 of the essay, I will share more concretely some case studies (two subtle and two stark) as well as provide more info about the games highlighted as they show up. I will also explore practical interventions as an attempt for how we might redistribute authority (and consequence) within fields and across sectors (and actors?). But, if we accept that redistribution is destabilizing, will it create new games? *[Some?] systems cannot be made honest without becoming something else entirely.

We will test the boundaries of these membranes, asking: Who decides? Who bears cost? What would have to move—in context or primacy—to enable systemic change in our field discourse and our field practice? Through these reflections we may arrive at some pathways for practitioners, bridgers, sensers and builders to reshape (or at least interrupt) the games that govern our social systems.

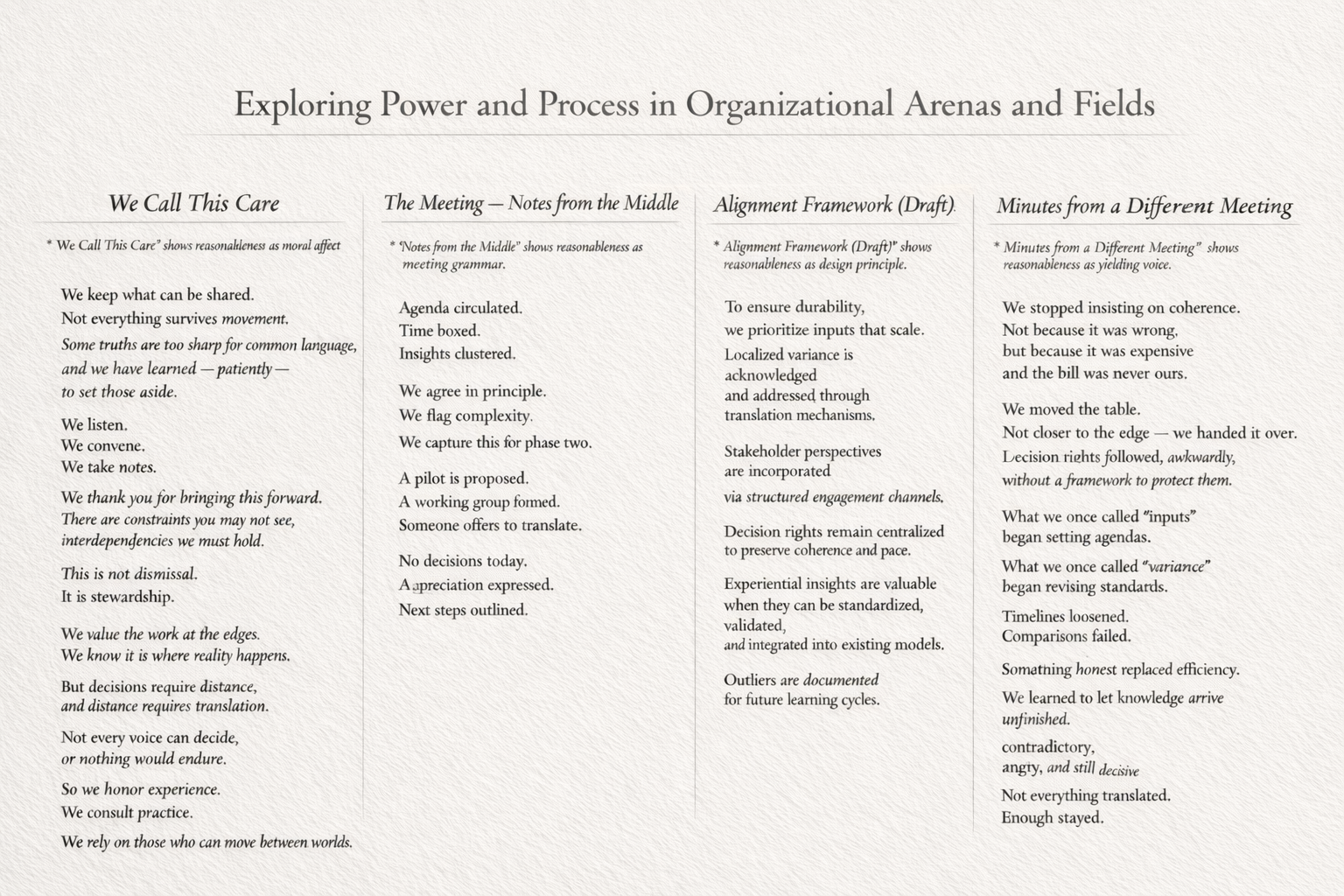

These four poems highlight ‘how fields speak’. The four poems are representative of four co-present voices: Justification, Process, Execution, Yielding Dorothy Coccinella Lady Bugboss identified how the fourth poem “gestures toward a transfer of ownership. Risk moves upstream. Standards loosen. The field changes owners”.

Footnotes

1 Circulates: insights repeated without decisional force.

2 Loss of air was used instead of the more visceral drowning to be respectful of the trigger that it might engage in readers. We hope that in doing this we preserved the moral compression that is perhaps distinct to bridgers and practitioners and those lower in the power differential but removed the violent imagery.

3 Legibility: translation into standardized forms

4 Travel: movement across boundaries into decision-making forums and authoritative documents.

5 Container: governance shell organizing funding, authority, and liability.

6 Mislocate power: mistaking consultation for decision rights.

7 Membrane: selective barrier regulating decisional force.

8 Reasonable: socially rewarded posture protecting continuity.

9 Qualified leadership: language such as 'Black leadership' or 'Indigenous leadership' marking leadership with identity qualifiers, while 'white settler leadership' remains unmarked; this asymmetry reveals embedded normativity in standards-setting power.

10 Travels upward: critique acknowledged symbolically without altering authority.

11 Metabolize harm: institutional absorption without redistribution.

12 Centralized decision rights: control over budgets, standards, consequences.

13 Risk flows downward: harm borne by practitioners or communities.

14 Owners: actors holding standards-setting power and liability.

15 Legitimacy: institutional acceptance enabling authority persistence.

16 Bridge: translational labor often resolving tension without shifting power.

17 Ledger: unacknowledged accounting of who pays when decisions fail.

18 Persist: continued reproduction of authority despite critique.

19 Contain: active management of dissent to prevent destabilization.

Further reading - references (by theme)

Field theory & practice

· Fligstein, N. & McAdam, D. A Theory of Fields. Oxford University Press, 2012.https://global.oup.com/academic/product/a-theory-of-fields-9780199859634

· Schatzki, T. The Site of the Social. Penn State University Press, 2002.https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/0-271-02100-0.html

· Star, S.L. & Griesemer, J.R. Institutional Ecology and Boundary Objects. Social Studies of Science, 1989.https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/030631289019003001

Field building & infrastructure

· ORS Impact. Not Always a Movement: What Is—and Isn’t—Field Building. 2020.https://www.orsimpact.com/

· Bridgespan Group. Field Building for Population-Level Change. 2020.https://www.bridgespan.org/insights/library/philanthropy/field-building-for-population-level-change

· Urban Institute. Exploring the Social Sector Infrastructure. 2021–2023.https://www.urban.org/

Learning, legitimacy & governance

· Argyris, C. & Schön, D. Organizational Learning II. Addison-Wesley, 1996.https://www.worldcat.org/title/35018742

· Argyris, C. Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, 1991.https://hbr.org/1991/05/teaching-smart-people-how-to-learn

· Vaughan, D. The Challenger Launch Decision. University of Chicago Press, 1996.https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo3626242.html

· Power, M. The Audit Society. Oxford University Press, 1997.https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-audit-society-9780198296034

· Shotter, J. Conversational Realities Revisited. Taos Institute, 2008.https://taosinstitute.net/conversational-realities-revisited

Case context

· CGAP. Andhra Pradesh 2010: Global Implications of the Crisis in Indian Microfinance. 2010.https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/andhra-pradesh-2010-global-implications-crisis-indian-microfinance

· Brookings Institution. Outcomes-based financing / impact bonds research collection.https://www.brookings.edu/search/?post_type=all&query=outcomes-based%20financing%20impact%20bond

· Center for Effective Philanthropy. Letting Lived Experience Lead the Way. 2022.https://cep.org/letting-lived-experience-lead-the-way/

Relational Context

My gratitude to Dorothy Coccinella Ladybugboss for showing me that when harm is not distributed, it concentrates. And it concentrates where authority is weakest. Dorothy accurately describes how “this essay is diagnosing something structural. It is tracing how authority stabilizes itself while sounding benevolent. It is naming the membrane between practice and power.”

AI Relational Use Statement

This essay was produced through iterative engagement with AI that required active correction, reinstatement of power analysis, and restoration of omitted structural elements. While AI supported drafting and assembly, authority over framing, interpretation, and final decisions remained with the author.

Consulting Invitation - Caprivian Strip Inc & Transition Bridges Project

If this terrain feels familiar — the membrane between consequence and authority, the tension between coordination and redistribution — we host structured conversations that surface these dynamics without collapsing into blame or abstraction.

We facilitate spaces where practitioners, builders, sensors, and bridgers examine power posture, temporal stance, and decision design together.

We support institutions exploring how to move from consultation to authority shift.

If you are asking: Who decides? Who bears cost? What would have to move? — that is the work.